Superwoman was already here.

And she gave us a superb educational model to end the “Race to Nowhere.”

Her name was Dr. Maria Montessori and in the first half of the 20th century she pioneered and refined the Montessori method of education. Today, there are over 17,000 Montessori schools worldwide including thousands of preschools in the USA and hundreds of Montessori schools in the U.S. at the K-8 level.

My children go to a private Jewish Montessori school in New Jersey called Yeshivat Netivot Montessori. After five years as a parent at Netivot, I now believe quite deeply that it is a national tragedy that Montessori is largely deemed to be an educational option only for privileged kids from families that can afford tuition at a progressive private school.

Millions more American children deserve access to a Montessori education.

There are about 350 public Montessori schools in the United States, a number that is shamefully small.

I am not writing to explain, “What is Montessori?” There are several good books, lots of internet videos and numerous websites to answer that question.

But I do want to offer three reasons* Why I love Montessori and believe that millions more American children could benefit from this extraordinary approach to teaching and learning:

1. Curiosity

In a Montessori classroom, questions matter more than answers and a child’s natural curiosity is welcomed, not shunned.

Newsweek ran an article last summer about America’s “creativity crisis” with this striking paragraph (emphasis mine):

“Preschool children, on average, ask their parents about 100 questions a day. Why, why, why—sometimes parents just wish it’d stop. Tragically, it does stop. By middle school they’ve pretty much stopped asking. It’s no coincidence that this same time is when student motivation and engagement plummet. They didn’t stop asking questions because they lost interest: it’s the other way around. They lost interest because they stopped asking questions.“

(some kids getting all Montessori with shapes. source)

In a Montessori school, this dynamic does not happen because teachers “follow the child” and are always encouraging the kids to ask questions. The Montessori method cares far more about the inquiry process and less about the results of those inquiries, believing that children will eventually master–with the guidance of their teachers and the engaged use of the hands-on Montessori materials which control for error–the expected answers and results that are the focus of most traditional classroom activity.

My daughter’s lower elementary teacher (Montessori classes are typically multi-age, lower elementary is grades 1-3 together) recently told me that a few kids in her classroom were learning about the triangle and they asked “Can a triangle have more or less than 180 degrees?” In classic Montessori style, the teacher turned the question back on them and said, “Use the hands-on geometric materials and try and make an actual triangle that is more or less than 180 degrees.” So the children have their question honored and arrive at the proper answer by themselves.

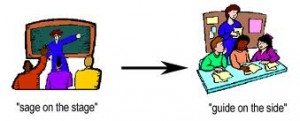

This story also highlights the role of a teacher in a Montessori classroom as being a “guide on the side” rather than the “sage on the stage.”

(can you believe that I found this on the internet? source)

In a world where the amount of information is doubling every 2.5 years (with much of it available at the click of a mouse) and where the top 10 in-demand jobs in 2010 did not even exist in 2004, encouraging kids to ask good questions and giving them life-long tools to investigate those questions is far more important than instructing them on how to produce correct responses. Even if those answers require some level of complexity, they are generally still straight-forward and predictable, which hardly prepares them for a world whose path is increasingly winding and unknown.

The culture of inquiry that is the hallmark of a good Montessori school is also a critical foundation for the creativity and innovation that America will need to compete in the 21st century. In December 2009, the Harvard Business Review published an article called, “The Innovator’s DNA” based on a six-year study of 3,000 creative executives including visionaries likeApple’s Steve Jobs, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Ebay’s Pierre Omidyar and Meg Whitman, and P&G’s A.G. Lafley. In an accompanying interview (with two of the three authors of the study) entitled “How Do Innovators Think?”, one of the professors that conducted the study noted (emphasis mine)

“We also believe that the most innovative entrepreneurs were very lucky to have been raised in an atmosphere where inquisitiveness was encouraged. We were struck by the stories they told about being sustained by people who cared about experimentation and exploration. Sometimes these people were relatives, but sometimes they were neighbors, teachers or other influential adults. A number of the innovative entrepreneurs also went to Montessori schools, where they learned to follow their curiosity. To paraphrase the famous Apple ad campaign, innovators not only learned early on to think different, they act different (and even talk different).”

2. No Homework

(source)

Many parents ask themselves, “If my child is spending six, seven or eight hours in school, why does she get so much homework?” If she were alive today, Dr. Maria Montessori would definitely be asking the same question.

My children do not have any daily homework at their Montessori school. While this varies at Montessori schools, most Montessori schools do not give kids any kind of daily homework. They may have research projects or long-term book reports (as do the students at my daughters’ Jewish Montessori school), but no daily homework.

The effectiveness of the Montessori approach usually obviates the need for homework. As one father in our school noted to me, “My 7 year-old was in a traditional school last year and he learns more in a day at this Montessori school than he did in a month at his regular school.” Since children in a high-quality Montessori school learn mostly by doing and by using as many of their senses as possible, in-school time is extremely productive and there is little or no requirement for homework to review and/or build upon their daily in-school lessons.

Without the crushing burden of homework that most American kids face each night, kids in a Montessori school are free to do whatever they like after school: play outside, watch TV, read, participate in sports, etc. The daily emotional battles over homework that most parents know all too well are also largely eliminated.

And homework is a waste of time. The research has shown consistently that homework at the grade school level has virtually no correlation with academic achievement. See this article from Time magazine which summarizes the leading research.

3. Calm and Peaceful Classroom Environment

Good Montessori classrooms have a sense of calm and order that is amazing; a setting where all kids are consistently engaged throughout the day in activities that they find meaningful and fun. We are starting to fully grasp how critical this type of environment is for learning and development, regardless of age. In the past three decades, there has been an explosion of important research that documents the connections between stress levels and the ability of a person to function and thrive, whether it be at home, work or school.

In a wonderful new book called “Brain Rules for Baby” by Dr. John Medina, a brain scientist, some of this research is examined and explored. Dr Medina, in a chapter on how to raise a smart child writes:

“First, I need to correct a misconception. Many well-meaning moms and dads think their child’s brain is interested in learning. That is not accurate. The brain is not interested in learning. The brain is interested in surviving. Every ability in our intellectual tool kit was engineered to escape extinction. Learning exists only to serve the requirements of this primal goal. It is a happy coincidence that our intellectual tools can do double duty in the classroom, conferring on us the ability to create spreadsheets and speak French. But that’s not the brain’s day job. That is an incidental byproduct of a much deeper force: the gnawing, clawing desire to live to the next day. We do not survive so that we can learn. We learn so that we can survive.

This overarching goal predicts many things, and here’s the most important: If you want a well-educated child, you must create an environment of safety. When the brain’s safety needs are met, it will allow its neurons to moonlight in algebra classes. When safety needs are not met, algebra goes out the window. Roosevelt’s dad held him first, which made his son feel safe, which meant the future president could luxuriate in geography.”

In Montessori classrooms, the methodology of engaging with children, the approach of the teachers and the way those teachers are trained all help build and foster this environment of safety where children can learn and flourish.

CONCLUSION

My commitment to my Jewish identity means that my kids need to go to a Jewish school so they can learn deeply about Judaism and their Jewish heritage. Every day I wake up grateful that an awesome Jewish Montessori school exists five minutes from my house in New Jersey.

But I am also an American who loves his country and cares deeply about all her children and their future, which of course will largely determine America’s future.

Our public education system needs radical transformation. Every child has gifts and talents that should be nurtured and we are wasting vast oceans of human ability and potential with our current system.

There are no silver bullets and I do not want to suggest that if every child went to a Montessori school, all of our educational challenges would be solved. Not every child is right for a Montessori school and Montessori is not right for every child.

But Montessori can be a great educational experience for many, many more American children and I urge all parents to spend two hours visiting a high-quality Montessori school, one that is certified by either the American Montessori Society (AMS) or Association Montessori Internationale (AMI)-USA.

There are an increasing number of public and charter Montessori schools. If your children do not live near one, then organize with other parents to demand that this approach be offered as an option in your school district. Get in touch with people from other cities who have found a way to provide this option to their children in a public school setting.

Superwoman arrived over 100 years ago and showed us how extraordinary school can be for all types of children. It is up to all of us to carry on her legacy and work. America’s children deserve nothing less.

(source)

* * *

Daniel C. Petter-Lipstein is the father of three children that thrive at Yeshivat Netivot Montessori, a Jewish Montessori school in NJ. He graduated from Harvard College and Columbia Law School and after a decade still finds satisfaction as a lawyer, though he sometimes wishes he could just take a month off and audit his daughters’ 4-6th grade upper elementary class where they are learning concepts like stellar nucleosynthesis and studying the history of marbles and creating their own marble games.

Additional notes from Daniel: The views and opinions expressed in this article are entirely my own. Not a single phrase, word or comma of this article was reviewed or approved by Yeshivat Netivot Montessori, AMS, AMI-USA or the Montessori Doughnut Plaza I plan to open in Laughing Waters, NY when I retire.

This article is dedicated in gratitude to Trevor Eissler, Montessori Dad and author of Montessori Madness, the best introduction and overview of Montessori available today (in my humble opinion). Thank you Trevor, for teaching me to embrace and cultivate my passion as a Montessori Dad.

*These are not the only three, just the ones that came together in my head as I wrote this article. There are dozens more, but Kate asked for an article/blog post, not a treatise, and she is my friend, so I listen to her.

And she gave us a superb educational model to end the “Race to Nowhere.”

Her name was Dr. Maria Montessori and in the first half of the 20th century she pioneered and refined the Montessori method of education. Today, there are over 17,000 Montessori schools worldwide including thousands of preschools in the USA and hundreds of Montessori schools in the U.S. at the K-8 level.

My children go to a private Jewish Montessori school in New Jersey called Yeshivat Netivot Montessori. After five years as a parent at Netivot, I now believe quite deeply that it is a national tragedy that Montessori is largely deemed to be an educational option only for privileged kids from families that can afford tuition at a progressive private school.

Millions more American children deserve access to a Montessori education.

There are about 350 public Montessori schools in the United States, a number that is shamefully small.

I am not writing to explain, “What is Montessori?” There are several good books, lots of internet videos and numerous websites to answer that question.

But I do want to offer three reasons* Why I love Montessori and believe that millions more American children could benefit from this extraordinary approach to teaching and learning:

1. Curiosity

In a Montessori classroom, questions matter more than answers and a child’s natural curiosity is welcomed, not shunned.

Newsweek ran an article last summer about America’s “creativity crisis” with this striking paragraph (emphasis mine):

“Preschool children, on average, ask their parents about 100 questions a day. Why, why, why—sometimes parents just wish it’d stop. Tragically, it does stop. By middle school they’ve pretty much stopped asking. It’s no coincidence that this same time is when student motivation and engagement plummet. They didn’t stop asking questions because they lost interest: it’s the other way around. They lost interest because they stopped asking questions.“

(some kids getting all Montessori with shapes. source)

In a Montessori school, this dynamic does not happen because teachers “follow the child” and are always encouraging the kids to ask questions. The Montessori method cares far more about the inquiry process and less about the results of those inquiries, believing that children will eventually master–with the guidance of their teachers and the engaged use of the hands-on Montessori materials which control for error–the expected answers and results that are the focus of most traditional classroom activity.

My daughter’s lower elementary teacher (Montessori classes are typically multi-age, lower elementary is grades 1-3 together) recently told me that a few kids in her classroom were learning about the triangle and they asked “Can a triangle have more or less than 180 degrees?” In classic Montessori style, the teacher turned the question back on them and said, “Use the hands-on geometric materials and try and make an actual triangle that is more or less than 180 degrees.” So the children have their question honored and arrive at the proper answer by themselves.

This story also highlights the role of a teacher in a Montessori classroom as being a “guide on the side” rather than the “sage on the stage.”

(can you believe that I found this on the internet? source)

In a world where the amount of information is doubling every 2.5 years (with much of it available at the click of a mouse) and where the top 10 in-demand jobs in 2010 did not even exist in 2004, encouraging kids to ask good questions and giving them life-long tools to investigate those questions is far more important than instructing them on how to produce correct responses. Even if those answers require some level of complexity, they are generally still straight-forward and predictable, which hardly prepares them for a world whose path is increasingly winding and unknown.

The culture of inquiry that is the hallmark of a good Montessori school is also a critical foundation for the creativity and innovation that America will need to compete in the 21st century. In December 2009, the Harvard Business Review published an article called, “The Innovator’s DNA” based on a six-year study of 3,000 creative executives including visionaries likeApple’s Steve Jobs, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Ebay’s Pierre Omidyar and Meg Whitman, and P&G’s A.G. Lafley. In an accompanying interview (with two of the three authors of the study) entitled “How Do Innovators Think?”, one of the professors that conducted the study noted (emphasis mine)

“We also believe that the most innovative entrepreneurs were very lucky to have been raised in an atmosphere where inquisitiveness was encouraged. We were struck by the stories they told about being sustained by people who cared about experimentation and exploration. Sometimes these people were relatives, but sometimes they were neighbors, teachers or other influential adults. A number of the innovative entrepreneurs also went to Montessori schools, where they learned to follow their curiosity. To paraphrase the famous Apple ad campaign, innovators not only learned early on to think different, they act different (and even talk different).”

2. No Homework

(source)

Many parents ask themselves, “If my child is spending six, seven or eight hours in school, why does she get so much homework?” If she were alive today, Dr. Maria Montessori would definitely be asking the same question.

My children do not have any daily homework at their Montessori school. While this varies at Montessori schools, most Montessori schools do not give kids any kind of daily homework. They may have research projects or long-term book reports (as do the students at my daughters’ Jewish Montessori school), but no daily homework.

The effectiveness of the Montessori approach usually obviates the need for homework. As one father in our school noted to me, “My 7 year-old was in a traditional school last year and he learns more in a day at this Montessori school than he did in a month at his regular school.” Since children in a high-quality Montessori school learn mostly by doing and by using as many of their senses as possible, in-school time is extremely productive and there is little or no requirement for homework to review and/or build upon their daily in-school lessons.

Without the crushing burden of homework that most American kids face each night, kids in a Montessori school are free to do whatever they like after school: play outside, watch TV, read, participate in sports, etc. The daily emotional battles over homework that most parents know all too well are also largely eliminated.

And homework is a waste of time. The research has shown consistently that homework at the grade school level has virtually no correlation with academic achievement. See this article from Time magazine which summarizes the leading research.

3. Calm and Peaceful Classroom Environment

Good Montessori classrooms have a sense of calm and order that is amazing; a setting where all kids are consistently engaged throughout the day in activities that they find meaningful and fun. We are starting to fully grasp how critical this type of environment is for learning and development, regardless of age. In the past three decades, there has been an explosion of important research that documents the connections between stress levels and the ability of a person to function and thrive, whether it be at home, work or school.

In a wonderful new book called “Brain Rules for Baby” by Dr. John Medina, a brain scientist, some of this research is examined and explored. Dr Medina, in a chapter on how to raise a smart child writes:

“First, I need to correct a misconception. Many well-meaning moms and dads think their child’s brain is interested in learning. That is not accurate. The brain is not interested in learning. The brain is interested in surviving. Every ability in our intellectual tool kit was engineered to escape extinction. Learning exists only to serve the requirements of this primal goal. It is a happy coincidence that our intellectual tools can do double duty in the classroom, conferring on us the ability to create spreadsheets and speak French. But that’s not the brain’s day job. That is an incidental byproduct of a much deeper force: the gnawing, clawing desire to live to the next day. We do not survive so that we can learn. We learn so that we can survive.

This overarching goal predicts many things, and here’s the most important: If you want a well-educated child, you must create an environment of safety. When the brain’s safety needs are met, it will allow its neurons to moonlight in algebra classes. When safety needs are not met, algebra goes out the window. Roosevelt’s dad held him first, which made his son feel safe, which meant the future president could luxuriate in geography.”

In Montessori classrooms, the methodology of engaging with children, the approach of the teachers and the way those teachers are trained all help build and foster this environment of safety where children can learn and flourish.

CONCLUSION

My commitment to my Jewish identity means that my kids need to go to a Jewish school so they can learn deeply about Judaism and their Jewish heritage. Every day I wake up grateful that an awesome Jewish Montessori school exists five minutes from my house in New Jersey.

But I am also an American who loves his country and cares deeply about all her children and their future, which of course will largely determine America’s future.

Our public education system needs radical transformation. Every child has gifts and talents that should be nurtured and we are wasting vast oceans of human ability and potential with our current system.

There are no silver bullets and I do not want to suggest that if every child went to a Montessori school, all of our educational challenges would be solved. Not every child is right for a Montessori school and Montessori is not right for every child.

But Montessori can be a great educational experience for many, many more American children and I urge all parents to spend two hours visiting a high-quality Montessori school, one that is certified by either the American Montessori Society (AMS) or Association Montessori Internationale (AMI)-USA.

There are an increasing number of public and charter Montessori schools. If your children do not live near one, then organize with other parents to demand that this approach be offered as an option in your school district. Get in touch with people from other cities who have found a way to provide this option to their children in a public school setting.

Superwoman arrived over 100 years ago and showed us how extraordinary school can be for all types of children. It is up to all of us to carry on her legacy and work. America’s children deserve nothing less.

(source)

* * *

Daniel C. Petter-Lipstein is the father of three children that thrive at Yeshivat Netivot Montessori, a Jewish Montessori school in NJ. He graduated from Harvard College and Columbia Law School and after a decade still finds satisfaction as a lawyer, though he sometimes wishes he could just take a month off and audit his daughters’ 4-6th grade upper elementary class where they are learning concepts like stellar nucleosynthesis and studying the history of marbles and creating their own marble games.

Additional notes from Daniel: The views and opinions expressed in this article are entirely my own. Not a single phrase, word or comma of this article was reviewed or approved by Yeshivat Netivot Montessori, AMS, AMI-USA or the Montessori Doughnut Plaza I plan to open in Laughing Waters, NY when I retire.

This article is dedicated in gratitude to Trevor Eissler, Montessori Dad and author of Montessori Madness, the best introduction and overview of Montessori available today (in my humble opinion). Thank you Trevor, for teaching me to embrace and cultivate my passion as a Montessori Dad.

*These are not the only three, just the ones that came together in my head as I wrote this article. There are dozens more, but Kate asked for an article/blog post, not a treatise, and she is my friend, so I listen to her.